![[News] South Africa Seen Risking More Frequent Unrest Without Reforms [News] South Africa Seen Risking More Frequent Unrest Without Reforms](https://cra-sa.com/media/news-south-africa-seen-risking-more-frequent-unrest-without-reforms/@@images/4419a7da-4ae3-4237-aa59-139dd67218d1.jpeg)

South Africa will probably experience more frequent bouts of violent protests unless the government fast-tracks growth-enhancing structural reforms, according to the Centre For Risk Analysis.

The country is reeling from a week of deadly riots and looting last month that erupted in the eastern KwaZulu-Natal province and the commercial hub of Gauteng after the jailing of former President Jacob Zuma. The violence marked the worst civil unrest in South Africa since the end of White-minority rule in 1994, and left 342 people dead and thousands of businesses looted or burned down.

The violence reflects an economy that has been “stagnant for more than a decade,” said Gerbrandt van Heerden, an analyst at the Johannesburg-based think tank. “A lot of the unrest that South Africa has experienced this year and before are connected to a failing state.”

Data shows there is a strong correlation between economic growth and social stability, and rioting and looting could become more prevalent in the next few years unless the authorities are serious about implementing reforms, Van Heerden said. Small business will likely suffer the most from frequent unrest and higher crime levels will weigh on South Africa’s ability to attract investment, he said.

Growing Discontent

Protests in South Africa are more frequent when economic growth is weak.

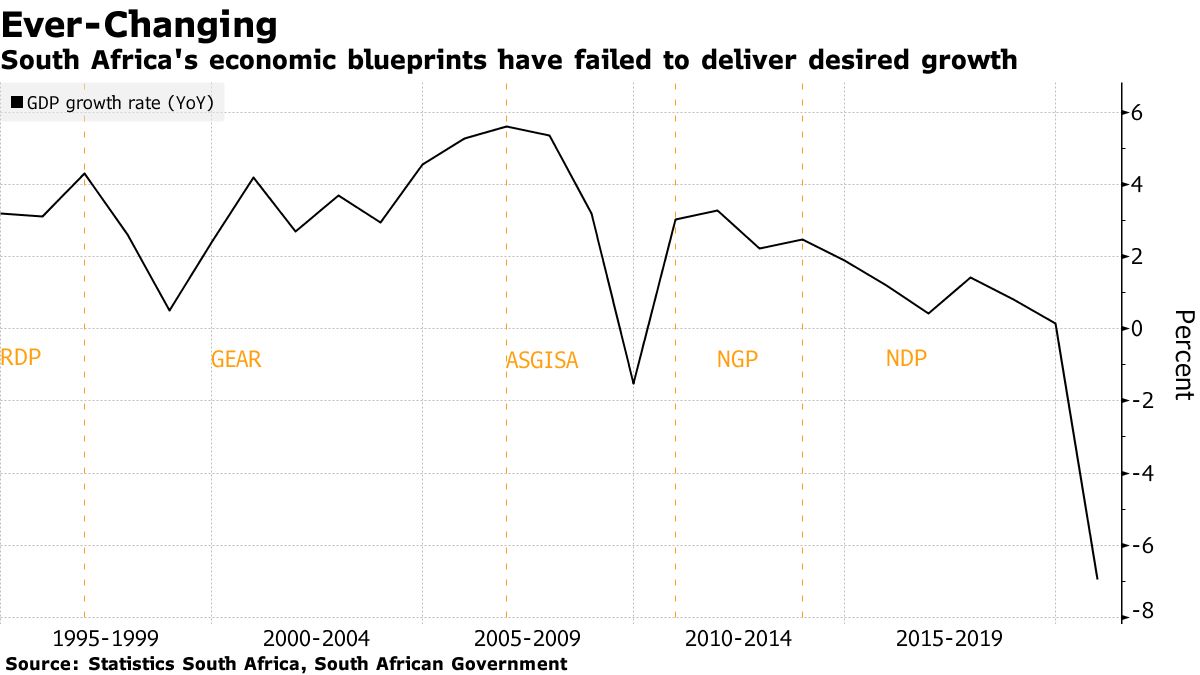

The government has formally adopted five blueprints to boost gross domestic product and job creation since the African National Congress won the nation’s first all-race elections 27 years ago. However, most of the policies have been stalled by powerful vested interests and policy paralysis, which left Africa’s most-industrialized economy stuck in its longest downward cycle since World War II even before the coronavirus pandemic hit output.

Reforms proposed almost two years ago by the National Treasury and the Economic Reconstruction and Recovery plan unveiled by President Cyril Ramaphosa in October are only now starting to show progress, including electricity generation by independent power producers and steps to ease port congestion. Other policy proposals the government has yet to implement include allocating broadband spectrum and speeding up visa access for tourists and workers with scarce skills.

GDP hasn’t expanded by more than 3% since 2011 and output is only expected to reach pre-pandemic levels in 2023. At 32.6%, South Africa’s official unemployment rate is the third-highest among 81 countries and the euro zone tracked by Bloomberg, though some data are for different periods.

Last month’s turmoil could cost the country about 50 billion rand ($3.5 billion) in lost output, according to the South African Property Owners Association. Economists see the damage shaving as much as one percentage point off economic growth this year.