![[Opinion] Redistributionism or Growth? [Opinion] Redistributionism or Growth?](https://cra-sa.com/media/opinion-redistributionism-or-growth/@@images/3e04ab2c-494a-4c21-a01f-7584c8214b07.jpeg)

Against the backdrop of a fiscus straining to return to a measure of soundness, a BIG will rapidly increase state dependency instead of employment. It is unlikely to be administered effectively by a state already struggling with welfare payments, and it represents numerous opportunities at all levels for abuse and cronyism.

In the aftermath of the first era of state capture, it would be deeply irresponsible to open up new avenues for government officials and bureaucrats to abuse their positions and influence, a risk that cannot be dismissed in the context of the ANC’s cadre deployment policy.

A new study, conducted by Intellidex on behalf of Business Unity SA and Business Leadership SA, found that government could raise at least R50 billion in new revenue to fund a BIG by increasing VAT from 15% to 17%. However, increasing VAT presents a serious electoral risk to an ANC already under pressure to retain its current majority.

Based on current reading and analysis, the ruling party is likely to achieve less than 50% in the national election in 2024, and burdening South Africans with even more extractive policies could lower the party’s electoral prospects further. The ANC can ill afford to give citizens more reasons to vote for its competitors.

Other tax increases

The report also looked at whether other tax increases could fund a BIG and found that the needed R50 billion could be sourced through an average increase of 5% on the country’s major three tax types – raising personal income tax by 1.2 percentage points for each bracket, upping corporate income tax to 29.5%, and boosting VAT to 15.75%. But the downstream impact on the country’s tax base would in all likelihood set the country even further back behind emerging-market peers in terms of economic activity and job-creation resources.

Increasing the tax burden on an already highly taxed, shrinking base increases the risk that highly mobile professionals with the required wealth and skills will seek to either emigrate or invest elsewhere.

That in turn means that the government will be under pressure to pursue precisely the kinds of policies the country can ill afford – for example, printing money or tapping pools of private savings to keep up with welfare payments, thereby weakening the Rand.

Rand weakness is currently one of the major drivers of the high inflation that all South Africans are experiencing.

South Africa cannot ‘redistribute’ citizens into prosperity; we do not have the fiscal room to do so. Meaningful prosperity can only be built on a foundation of wealth-creating policies, which are downstream from the ideas and ideology that inform them.However, getting the growth fundamentals right will mean abandoning ideas and policies grounded in state centralisation, intervention and control. It is unlikely that such a radical move will come from the ANC; the chances are much higher in a coalition or opposition context.

The fundamentals that the country must pursue include reforms and opportunities such as fuel price deregulation, electricity competition, the investment-ensuring strengthening of property rights by abandoning efforts to introduce expropriation without compensation, and dropping protectionist Localisation Master Plans. The latter in particular are likely to increase costs across the board and will add to inflation pressure if implemented.

Increasing frustration

Continuing with the current redistributionist, fixed-wealth path will mean that the most pressing concerns of South Africans – which our polling shows to be jobs, crime and service provision – will remain fundamentally unaddressed. This in turn means increasing frustration with both government and the status quo, and such frustration will continue to manifest in violent protests.

The country’s debt-servicing costs have grown to such a level that they will soon be second on the expenditure list. At the moment education is the biggest item, followed by social protection (mostly grants). Given the country’s low credit rating, taking on even more debt is a risky move. Introducing a BIG sets South Africa up for failure, especially when global events conspire to depress commodity demand and prices. (Lower growth prospects for the EU and China, South Africa’s two major export markets, already flag the risk that the country’s commodity windfall is running out).

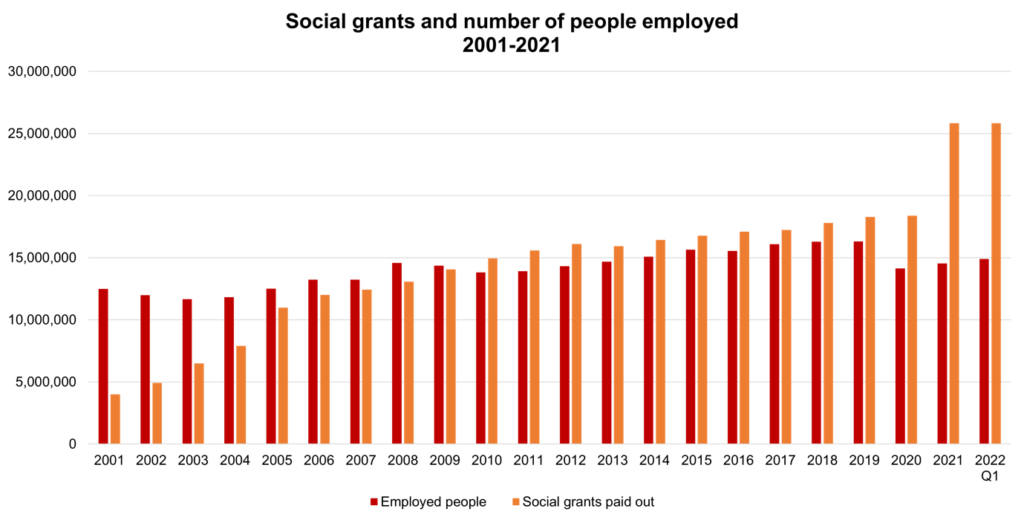

A real achievement would be to increase the number of people in employment, so that they can bake their own wealth cakes, take care of their families and communities, and have more disposable income to invest over the long term.