![[Opinion] Budget bottom line: SA is living on borrowed time [Opinion] Budget bottom line: SA is living on borrowed time](https://cra-sa.com/media/opinion-budget-bottom-line-sa-is-living-on-borrowed-time/@@images/ae439985-24fd-4369-ba82-117735787bb2.jpeg)

This is our overriding sense of South Africa’s economic circumstances in light of what emerges from the National Budget for 2021/22, tabled in Parliament this week.

In the latest edition of the Macro Review from the Centre For Risk Analysis, we unpack the budget, and identify the risk of South Africa’s deteriorating fiscal position.

Revenue collection was buoyed somewhat by a favourable international environment, with increased global demand for commodities boosting earnings for domestic mining firms. Consequently, the government collected revenue of R1.3 trillion in 2020/21, R99.6 billion more than it projected in the Medium-Term Budget Policy Statement (MTBPS) of October last year.

Treasury now expects to collect R1.5 trillion in 2021/22. However, our sense is that collections will diminish over the medium-to-longer term, owing to a low domestic growth outlook, as well as a shrinking tax base (exacerbated by skills and capital flight).

Meanwhile, consolidated expenditure continues its upward trajectory, with government spending set to rise to R2.02 trillion in 2021/22. Treasury predicts expenditure to stabilise at R2.09 trillion in 2023/24, but, as we often remind our clients, Treasury projections tend to suffer from over-optimism.

Minister Mboweni was quick to point out that ‘this is not an austerity Budget’. Notwithstanding, he is seeking to reduce expenditure by R264.9 billion over the medium term.

Cadre deployment

We doubt this will happen, given the reluctance of the government to reduce the size of the civil service, which has ballooned in recent years. Our reasoning is simple: cadre deployment is a centrepiece of government policy, but it would not work if cadres were to be retrenched.

Turning off the money taps would disrupt the internal unity of the party.

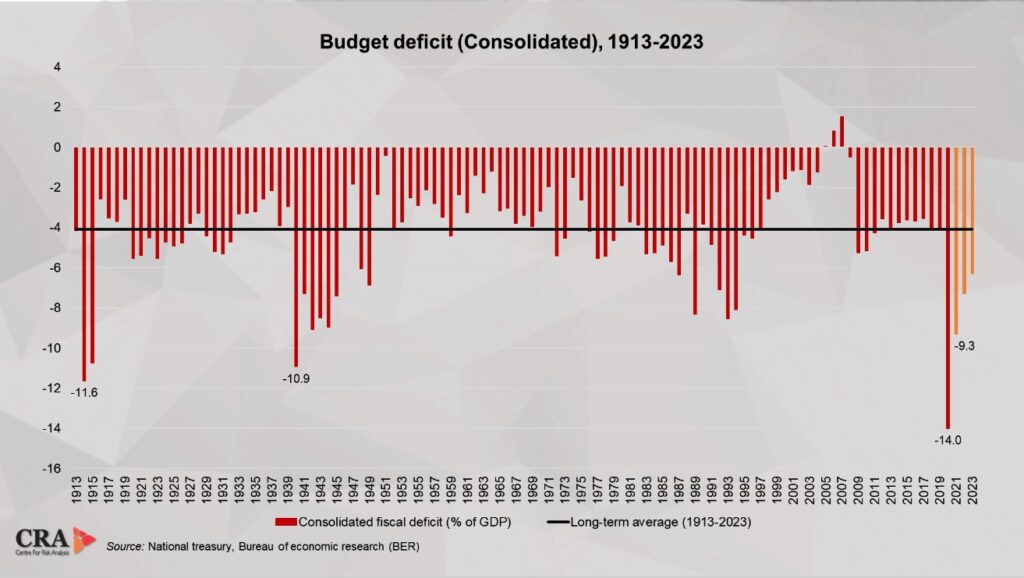

The budget deficit is projected to recover somewhat from the enormous post-Covid deficit of -14% in 2020 to (still large by historical standards) -9.3% in 2021. To finance the deficit, government borrowing will continue to surge to record-high levels.

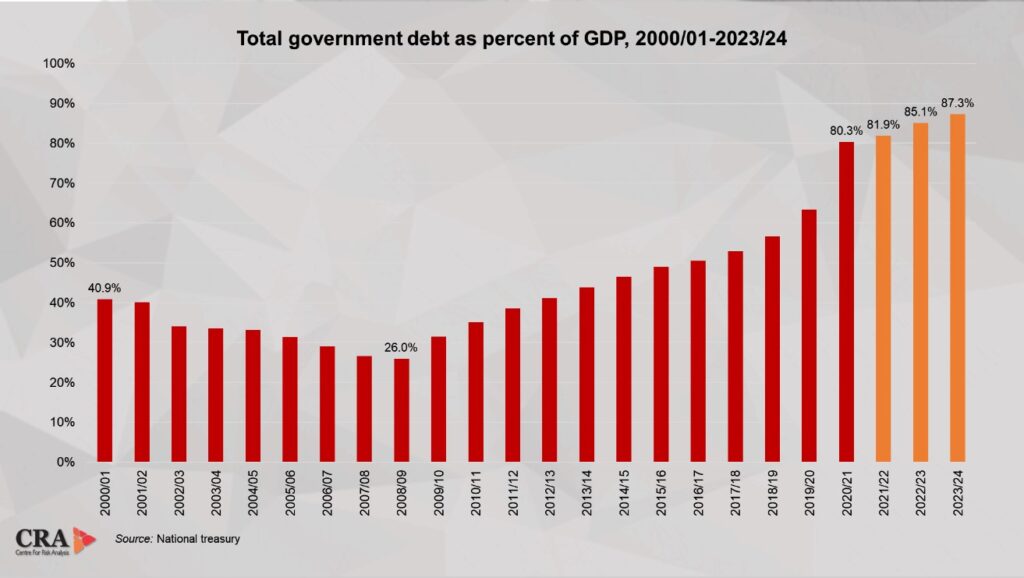

Sovereign debt is projected to reach 81.7% of GDP in 2021/22 and to rise significantly to 87.3% in 2023/24. Recall that debt-to-GDP levels were at 63.3% only two years ago, in the 2019/20 Budget. Debt service costs now amount to R269.7 billion or 13.3% of expenditure (meaning the government now spends more on debt payments than it does on the entire national health budget).

The Minister made much of plans to invest R791.2 billion in a government-led ‘infrastructure investment drive’.

South Africa’s infrastructure is certainly under strain, but so are its finances, and infrastructure development is no panacea for low growth. Only substantive reforms to the labour market and empowerment policy will lead to growth, but these will not be forthcoming. We caution South Africans to keep a watchful eye on imminent amendments to Regulation 28 of the Pension Funds Act, which the Minister suggested would ‘make it easier for retirement funds to increase investment in infrastructure.’

Through the back door

As the government runs out of money, this may be a way for it to quietly introduce asset prescription through the back door, as calls from within the Tripartite Alliance to ‘unlock’ private pension funds have not abated.

The deterioration in the fiscus is unlikely to dissuade foreign investors, who remain hungry for high-yield emerging market bonds. Given that yields are low in the developed world, and that South Africa’s budget deficit is relatively cheap in US dollar terms, investors will continue to buy South African government bonds. This could provide an artificial boost to the Rand, which is likely to hold its current levels into the short-to-medium term (although our medium-to-longer term Rand outlook remains one of sharp weakening).

Overall, then, while taxes remained mostly unchanged, and the global environment relatively favourable, our sense from the Budget is that, in the absence of policy reform and fiscal prudence, the government really is increasingly living on borrowed time.